Part 4: Registering services and using the Service Locator

This part of the article series focuses on details of the configuration options available when using coon.core.app.Application from the coon.js-package; namely the services-configuration option that lets you define services that can be queried using coon.core.ServiceLocator, providing a central registry for concrete classes mapped to abstracts.

The previous part of this article series provided an extended look at the various configuration options of a coon.js-application. This article assumes that you are familiar with the topics covered therein.

What is a Service Locator (and why)

If you’re not familiar with the concept of Service Locators, Martin Fowler has a very good introduction to this design pattern over at his blog:

Inversion of Control Containers and the Dependency Injection pattern

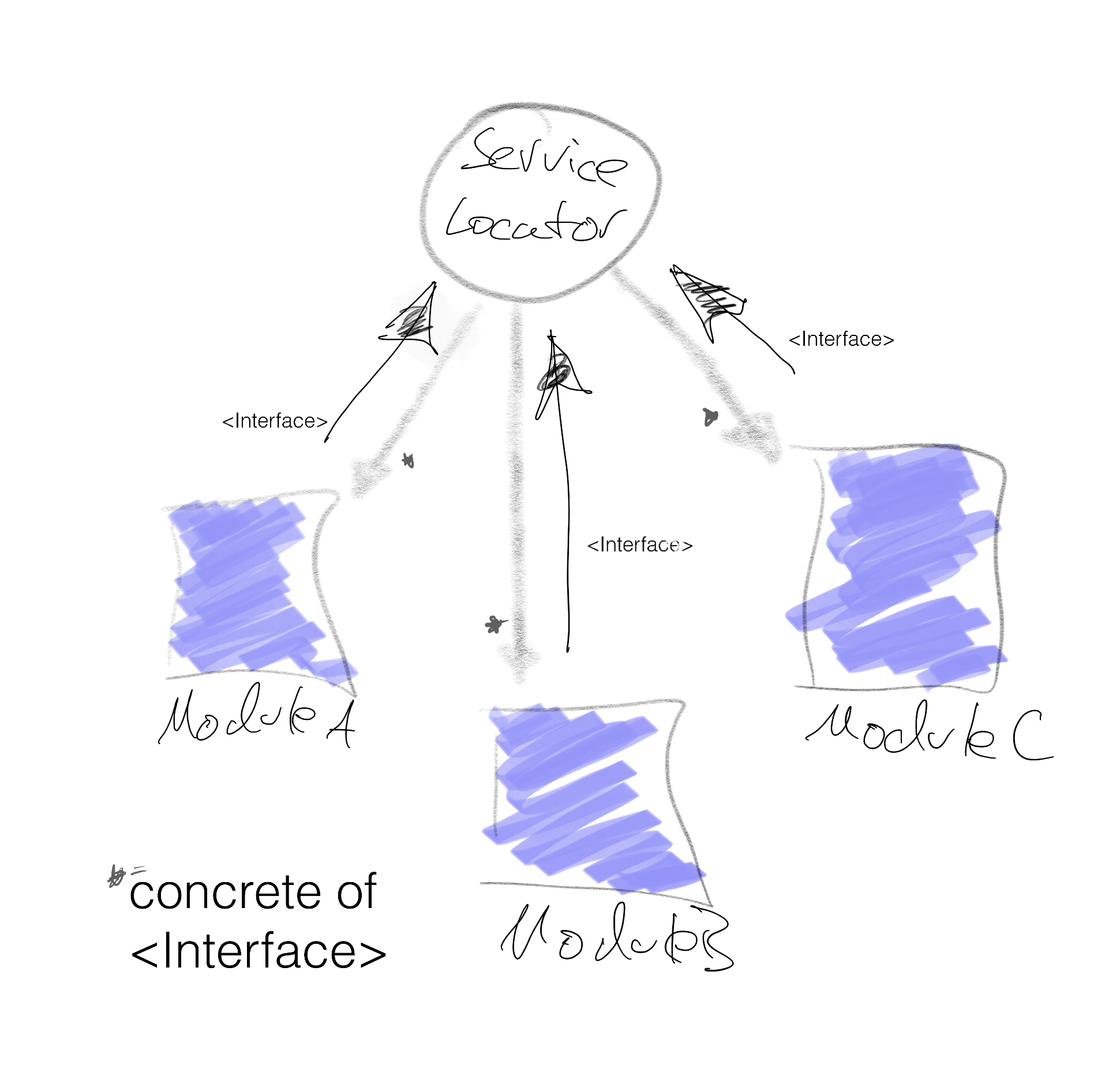

In Short, a Service Locator allows for separating large sections of a software. It represents a central registry that is known by every section in the software. Decoupled and unaware of each other, those sections are still able to use one and the same functionality during runtime by querying the Service Locator for concrete implementations of abstracts which describe their required functionality.

Simple use case — An Image Service

Let’s assume that we have various modules in our application: An email module, an address book and a SignIn-Manager. Each module has the functionality to show an image that is associated with a person — a profile picture. Now, each module understands the entity “person” in a different way:

For the email module, persons are identified by the information found in the from-header

The address book identifies a person by contact-information stored in various fields: firstname, lastname, address and so on. Of course, an address book’s user-entry also has an email address.

The SignIn-Manager identifies a person (a “user”) by an username and a password. For our use-case, the username must be the user’s email-address

So while all modules are aware of an entity representing a “person”, each module models this entity in a different way. However, each module requires the functionality to show a profile picture associated with a person.

Of help is a common identifier that is usually unique for a person — the email address.

The modules do not know where a profile picture for a person comes from. What they do know is

a profile picture can be uniquely associated with an email-address (1:1)

how to render a profile picture on the screen

that a Service Locator exists for querying services

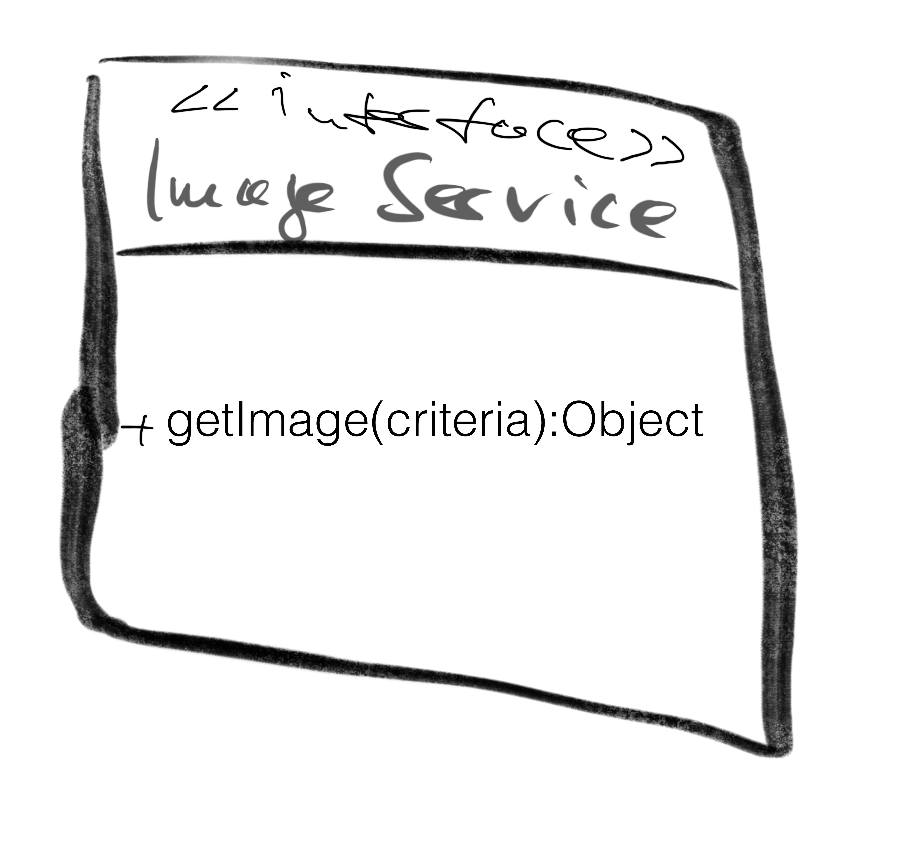

The common functionality for retrieving image data associated with an email address is given by the following interface:

Using JavaScript and coon.js, the implementation of a Service Locator is toned down compared to strongly typed languages, such as Java. It follows the same purpose however, and implementing APIs can add or remove abstractions and type checking as they like.

For our purpose, the final implementation in each module would look like this:

const criteria = {emailAddress: "user@domain.com"};

return coon.core.ServiceLocator

.resolve("ImageService")

.getImage(criteria);

Our search criteria is an object the ImageService understands, and we expect the coon.core.ServiceLocator to correctly resolve from ImageService to a concrete instance implementing this interface, properly responding to our API-calls when requesting image data.

The question that remains is: How do we configure the Service Locator so that it resolves to a concrete instance for a given abstract — in our case, a concrete of ImageService?

Configuring Services

Without the help of a DI Container, the scaffolding of services is done in the application configuration file — mapping class names of abstracts to their concrete representants; building up on the previous article about configuration of application instances, you might remember similar approaches regarding plugins, where class names of plugins are specified that get later on created during runtime. Thus, we are now introducing the services property for the application configuration file.

The following code block is part of an application configuration. The services-key denotes the section where abstracts are mapped to concretes — along with additional arguments that will be passed to the constructor of the service. Each service defined in here is treated as a shared instance — that means, for all modules across the application, the ServiceLocator will return one and the same instance of this class.

"services": {

"coon.core.service.UserImageService": {

"xclass": "coon.core.service.GravatarService",

"args": [{

"parameters" : {"d": "blank"}

}]

}

}

In the given example, the application registers coon.core.service.GravatarService — a specific of coon.core.service.Service for abstracts of the type coon.core.service.UserImageService. Whenever the ServiceLocator needs to resolve coon.core.service.UserImageService , one and the same instance of coon.core.service.GravatarService is returned — which was initially created with the constructor arguments {parameters:{d:"blank"}} :

// registering the GravatarService with the ServiceLocator

coon.service.ServiceLocator.register(

"coon.core.service.UserImageService",

Ext.create(

"coon.core.service.GravatarService",

{parameters:{d:"blank"}}

)

);

// later on, the GravatarService is returned for calls to:

const imgService = coon.core.ServiceLocator.resolve(

"coon.core.service.UserImageService"

);

Disadvantages of using Service Locators

The service locator is considered to be an anti-pattern. Mark’s arguments are definitely valid. I would not go so far and say that he is wrong — in a world without DI Containers, but with good source code documentation, I’d say it’s an okayish tool for the job, if you can live with the side effects global registries are prone to cause:

Our code must consider the fact that a service is missing. As a possible solution, the ServiceLocator could provide a concrete default (a “Special Case”) of the abstract, where applicabable. On another note, while we can guarantee that services resolved to specific abstracts are of the type of this abstract, the API of those services might not respond to our queries in a way the requesting API can handle the responses properly: Services might become very fine granular with their responses. This could lead to over engineering those services when considering various use cases (our ImageService, for example, might have to provide various binary formats for requested images, or none at all — the src-attribute of an HTML img-tag accepts an URL-string as well as base64-encoded data urls in the form of data:[<mediatype>][;base64],<data>).

Update 05 March 2023

If you feel the Service Locator is too clumsy, you can use an DI-Container for Ext JS, which I've written shortly after I have finished this article: Dependency Injection in JavaScript