Part 2: Packages and Configuration Options

In the previous part of this article series I gave a brief introduction to the coon.js framework — a “Toolset for rapid Sencha ExtJS application building”.

Now it’s time to present the general idea behind the framework and shed some light on the features it provides. In this Part 2, we’ll take a look at package management- and with coon.js, this means dynamic package loading and providing configuration options for packages.

Hardwiring is so 2001

Resolving application dependencies became more convenient with the introduction of package managers, such as Composer (PHP) and NPM (mainly JavaScript).

If you remember the early days of Sencha ExtJS, you might think of the “package manager” that was introduced with ExtJS 4 .2 and Sencha CMD 3.1— which was never really successful when you look at it from the external- dependency-managagement-and-centralized-repository-for-3rd-party-code-point of view (phew!). Sencha ExtJS Packages have always been a tool for organizing your code into smaller, more deliverable, reusable chunks and might have been a good way to maintain company code for various projects, but it was never flexible enough for providing dependency management of 3rd party code we have been looking for many, many years, and where Sencha obviously missed to jump the bandwagon once the time was right.

Sencha CMD packages were never flexible enough for providing real dependency management with Sencha projects.

JavaScript development got a lot more easy with NPM. However, Sencha is still locked deep in the basement together with Java and Ant, and getting things to work with Sencha CMD (on which ExtJS obviously still depends on) rather than Babel (for transpiling) and NPM can be quiet troublesome. The Sencha PackageLoader makes it all more bearable, but if you’re looking for a solution for dynamic package management with Sencha ExtJS, you have to add a few workarounds and be patient when wrapping your head around error messages that basically give no hint about what really went wrong when sencha app build fails with cryptic console output.

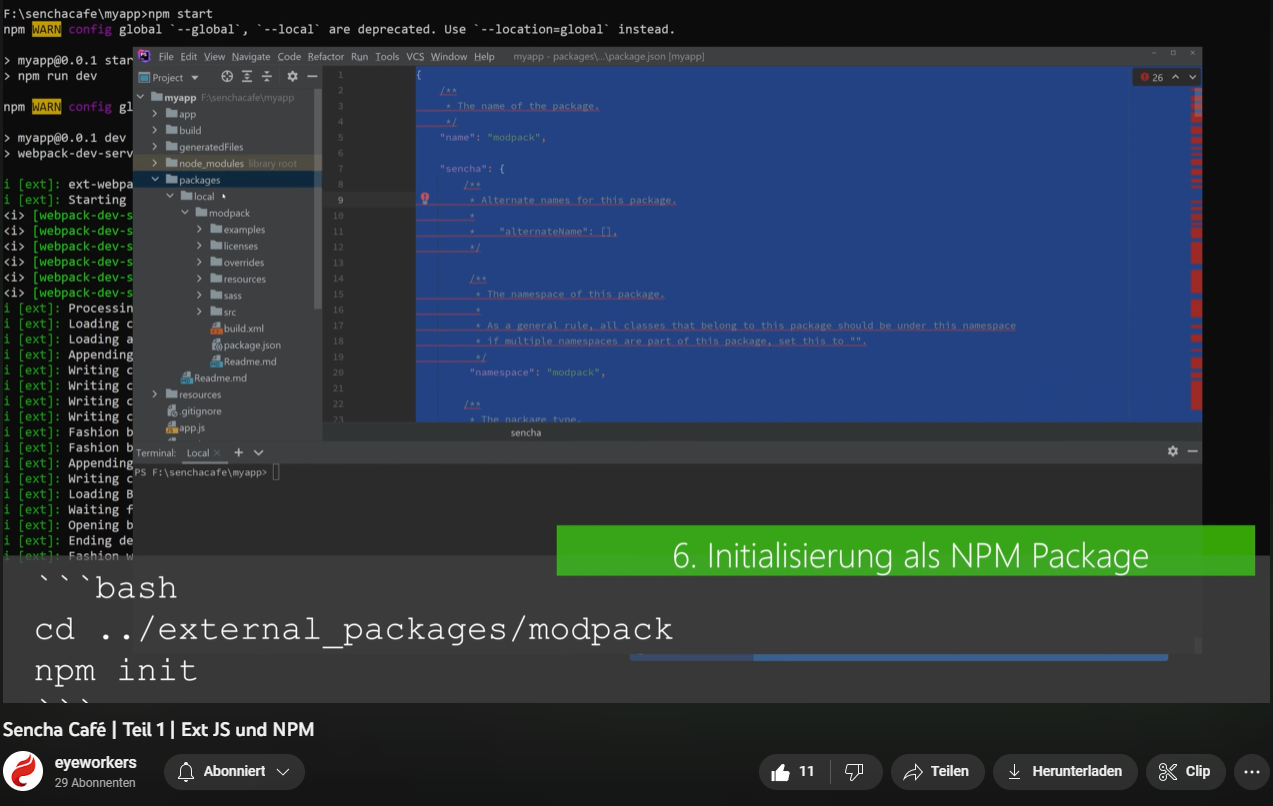

A brief introduction to Sencha Ext JS and NPM can be found here:

Sencha applications and dynamic packages

The Sencha Package Loader allows for dynamic package loading (hence the name), although these packages have to be linked against the application: exposing information about the requirements of an application comes with the expense of more configuration. Not only has the app.json to know what packages might(!) be used with your software — which contradicts the use case of over-the-air drop-ins of additional functionality—you also have to adjust your build process with specific flags so that the packages get properly build: sencha app build production --uses

However, combining the Package Loader with NPM and some customizing leverages ExtJS application building. Here comes coon.js into play.

coon.core.app.Application

To reduce bloat and make it possible to dynamically opt for eventually used packages, I wrote a specific of Ext.app.Application that is capable to read out package configuration during the startup of an application, making it easy to hook into the startup process of an app and decide what kind of packages have to be registered with the software, and — additionally — load package information from external files, providing runtime contexts to make sure various environments and their respective configurations can be considered.

This all might sound overwhelming at first, but it follows a very straightforward scheme: Read out information about registered packages, decide whether they should be loaded and apply their configuration from an (external) resource.

The payload for using this approach is that the developer needs to adopt a rethinking of how to set up an ExtJS app: With coon.js, it now largely consists of — often context-agnostic and self-contained — packages (you can also call them modules); except for core-functionality and themes, of course: Those are still hardwired to the application.

Configuration

Lets start on the very top and have a look at the configuration available with coon.js. Notable, the app.json allows for an additional configuration that will be considered for the configuration of underlying packages — the coon-js-configuration:

...

"name": "conjoon",

"production": {

"coon-js": {

"env": "prod",

"resourcePath": "coon-js"

}

},

"development": {

"coon-js": {

"env": "dev",

"resourcePath": "coon-js"

}

}

...

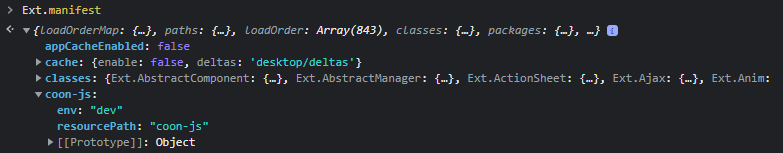

In both the production- and the development-section of the app.json, we have added a new property named coon-js, which allows for specifying coon.js-relevant application-configuration; we can read this later out of the Ext.manifest-object available during runtime of our Ext JS-application.

So, what will this be later used for? coon.js will look up the environment the application is built for (we are utilizing development/production build options of ExtJS here) and consider further configuration-loading given the env-value, making it possible to load configuration files specific for the development- or production-environment. For example, the development-environment can hold additional configuration options for Simlets used with the dev-build (mainly for mocking a backend API), while the production-configuration holds REST-endpoints and the like for — well, exposing environmental information of the application in production mode. More use-cases at the end of this article.

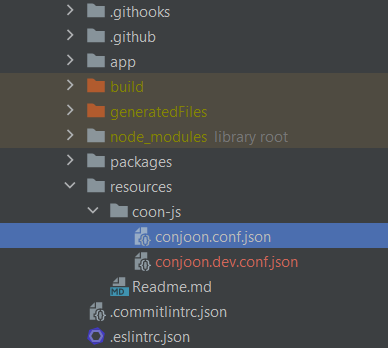

The resourcePath denotes the name of the folder in which coon.js should look up configuration files — this is the folder that should be made available in the resources-directory found in the base installation of an ExtJS-application: Further Sencha specific configuration options for this folder can be found in the resources-section of the app.json.

But what files are considered as configuration files? Somehow the application must now which files to load, and this is realized using a specific naming pattern coon.js will look up.

Application configuration files

First off, you have a global, application specific configuration file. This file must be named after the application coon.js is configured for, followed by a postfix that denotes the environment for which it was created, and the usual .json file-ending so that code-editors and the like know how to parse and syntax-highlight its contents. The pattern is:

[application_name].[environment].conf.json

In the above example for the app.json, we have specified that the shorthand for the production-environment is prod, while the shorthand for the development-environment is dev. The name of the application is conjoon. The configuration files must therefore be saved under any of the following names in order for coon.js to recognize them:

-

"env": “dev"conjoon.dev.conf.json - configuration loaded for development builds

-

"env”: “prod" conjoon.prod.conf.json — configuration loaded for production builds (note: this naming schema is currently in discussion, see link below)

-

conjoon.conf.json - configuration loaded if no environment specific configuration file was found

refactor: configuration files for prod must not use "prod" as infix · Issue #55 ·…

We will not go into the details about possible configuration options considered by coon.js for now — the 3rd part of this article series will take care of this — but a basic template with the most important sections of an application configuration file looks like this:

{

[application_name] : {

"application": {},

"plugins": [],

"packages": {}

}

}

All configuration-options specified in the application-section will be generally made available during runtime and can later on be queried via coon.core.ConfigManager.get([application_name]) (unaware packages can query [application_name] using the coon.core.Environment-class, if needed: coon.core.Environment.getManifest("name")).

Of course, other configurations sections are available to the coon.core.ConfigManager: they are queryable “domains”. For example, dynamic packages and their configuration (if specified) are always accessible using coon.core.ConfigManager.get([package_name]).

Package configuration files

The whole idea behind coon.js is to provide a system where applications load external and customizable packages on demand — so it would be a bad idea to not provide configuration options for these packages itself.

Similiar to the app.json, information about the package used by a coon.js-driven application must be placed in the package.json of the owning package. This has to be done using the sencha-section in the file, so the configuration is available later via Ext.manifest and does not collide with any NPM configuration:

{

// ... this is NPM-land

"sencha": {

// ... and this is Sencha-country. Most of this will

// end up in Ext.manifest

}

}

Again, we have to specify a coon-js-section in the package.json itself that holds various information about the package and how it should be treated by the owning application, such as

-

should the package be auto-loaded during application startup?

-

should the package’s PackageController (if available; it’s a specific of Ext.app.Controller) be registered as an application controller?

-

does the Package define configuration, and where can this information be found?

Here’s an example of the package.json from https://github.com/conjoon/extjs-app-webmail, the email client for conjoon:

{

"name": "@conjoon/extjs-app-webmail",

"sencha": {

"name": "extjs-app-webmail",

"coon-js": {

"package": {

"autoLoad": {

"registerController": true

},

"config": {

// ... here be package relevant config

}

}

},

"namespace": "conjoon.cn_mail",

"type": "code",

...

The 3rd part of this article series will focus on key-properties of the configuration, for now let’s have a quick look at a few properties presented with the example: autoLoad tells whether this package should be loaded upon the startup of the application and can be further configured — in this case along with registering the package’s PackageController — and the config-section provides all the necessary configuration for the package itself, queryable during runtime.

While it is totally valid to provide all the configuration information in the package.json itself, maintaining often-changing configuration can be quiet a hassle using this file: You have also the option to specify an individual file representing the package’s configuration — convenient in case you have to provide lots of configuration information.

It is also possible to omit the configuration here or in a separate file and move all the configuration details to the **application configuration file **— making it more convenient to edit multiple package configurations at once without having to manage file changes ( git commit package.json -m “feat: add config option for project X”) throughout various separate projects (if your package is used across multiple projects, that is). Remember the application configuration file template from the previous section of this article? Let’s tune the packages-section:

{

[application_name] : {

"plugins": [],

"application": {},

"packages": {

"extjs-app-webmail": {

"autoLoad": {

"registerController": true

},

"config": {

// ... add package relevant config HERE

}

}

}

}

}

Loading Packages

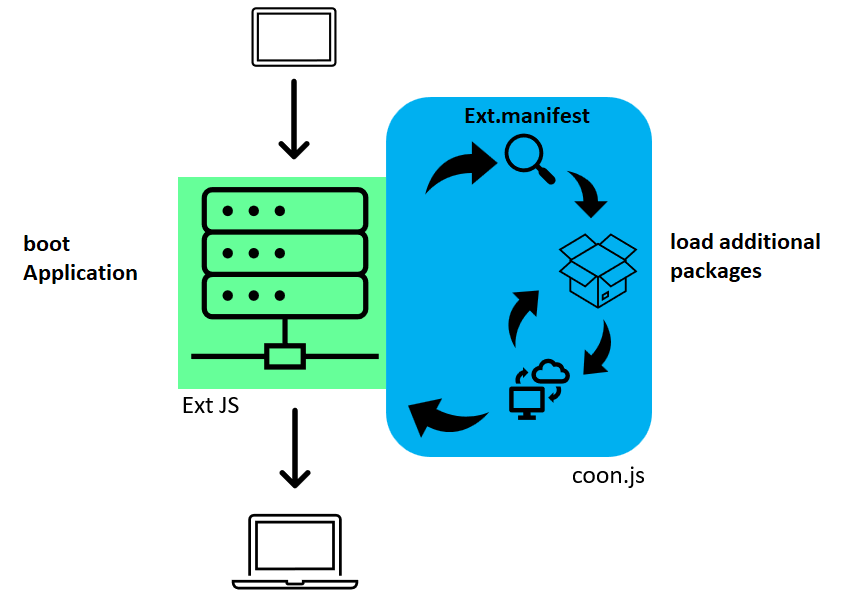

Given what we know about the configuration options, let’s have a look at how coon.js decides whether a package should be loaded dynamically.

First and foremost, we have to take care of two thing: Tagging the package as a coon.js-package and inform our app about the package-requirement in the uses-section in our app.json. While the latter is a necessary requirement for the ExtJS internal Package Loader (you can read more about the internals here), tagging the package as a coon.js package itself is required so that the package can be identified and treated as a package containing further, yet to be loaded, configuration.

The whole process simplified:

-

Application boots and loads requirements

-

coon.js hooks into the process, looks up and parses available package.json from any package available to the application

-

if a package is tagged as a coon.js package (i.e. has a coon-js-section), configuration for this package will be looked up and parsed

-

if a PackageController should get registered, it is registered with the application

-

launch()

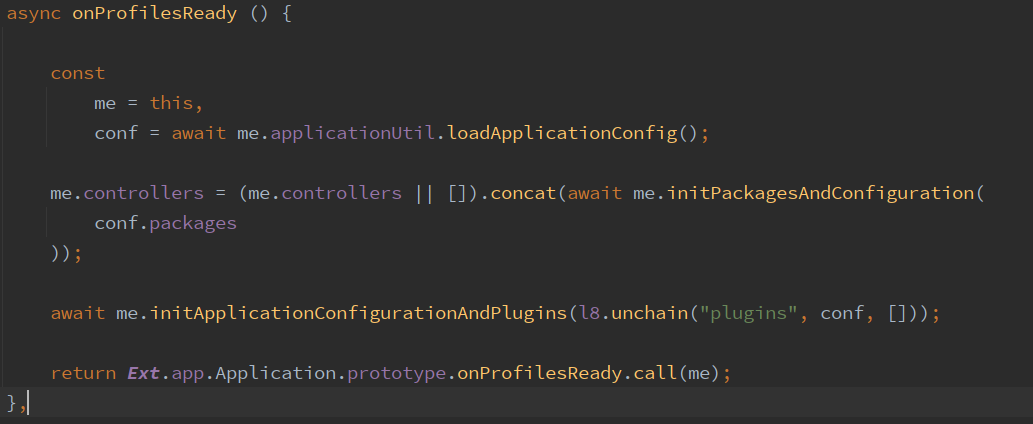

In order for this to work, the developer has to extend from coon.core.app.Application which is a specific of Ext.app.Application — its onProfilesReady will then initialize the packages and their configuration and set up all the required controllers, additionally configure and ready up any plugins that should be used with the application.

As mentioned earlier, packages that might get used later on must be exposed using the uses — configuration property in the app.json — this is so the meta-data of the packages can be found in the Ext.manifest-object later on.

Simple use cases

Here are a few use cases that will give you an idea how to use dynamic package loading and configuration using coon.js.

Different Packages for dev and prod environment

If you are a famlliar with building frontend systems, you are often confronted with Schroedinger’s backend systems — backends required by the app, but no one knows if they exist yet (except perhaps for the developer responsible for its implementation)! Required for your work and for processing incoming and outgoing data, a predefined data-structure and some dummy data is fine for setting up POCs and tests, but once you need to test your frontend given more lively conditions, you need more “real” data. For this purpose, the Ext.ux.ajax.SimManager exists, and I can not state often enough that your project should use it directly from the beginning — it has saved our company precious time in the past. A *SimManager *allows for managing mocked data endpoints of services for your software during development: You can wire all your requests as if they are actually existing in your code, but once requested, you’re not really connecting to a backend API over http: Instead, the SimManager takes care of re-routing requests to internal JavaScript classes which will then look up any data previously defined given a specific URL-pattern. (Using React, you can fall back to the wonderful Mirage project ; you can catch up on the topic regarding mocking APIs reading this article by @shashiparakramasinghe).

Using coon.js, we are able to simple attach and detach simlets in our development environment respective production environment. In our development section of the app.json we would define those packages representing simlets in the uses— array, while we optionally priovide url configuration in the associated configuration. A PackageController that is autoloaded into the application will then take care of configuring and registering the simlets with the ExtJS internal SimManager. Given the configuration options, the simlets can also exist in production builds — changing a value in the configuration file lets you easily enable or disable them individually.

Enabling/disabling Packages for different Builds

By simply providing declarative configurations using the configuration system, software project maintainers or administrators can easily enable or disable specific functionality for the application. Following SOC, an application should not break if simply disabling a package representing a module for our software (if it does, we must have done something wrong during development and rethink our approach to coupling and decoupling).

Hot-swapping functionality

Ever dreamt of adding/removing packages to a Sencha application without the need of rebuilding it completely? By utilizing the package-build commands of Sencha CMD we can build packages and drop them into a production build of a Sencha application built with coon.js — or remove any of them completely. This makes it possible for users to simply add and remove 3rd party packages on their own, without having to touch any existing code base (except for Ext.manifest, which must be aware of additional packages that are available for the software. But this is enough material for another article…)

The next part in this article series will provide a detailed look at the configuration options available with coon.js and how to use it with packages.